THE MAZE OF GLOBAL M&A

By Udayan Gupta

Cross-border M&A is once again on the rise. But completing a successful deal is increasingly complex and fraught with political, and other, risks.

At first glace, it seemed like another classic cross-border done deal. In November 2012, HSBC announced that it would be selling its stake in China’s Ping An Insurance to Thailand’s CP Group for $9.4 billion. The deal would be financed 21% by the CP Group’s own capital and 79% by cash and financing from China’s state-owned China Development Bank. HSBC even planned to book the sale as a $3 billion gain. But by last month all the moving pieces seemed to have come to a grinding halt. Chinese news media reported that part of the 21% of the CP Group’s “own cash” came from Chinese financier Xiao Jianhua. And the Chinese development bank said it had changed its mind about lending to the CP Group, controlled by Dhanin Chearavanont, reportedly Thailand’s richest man.

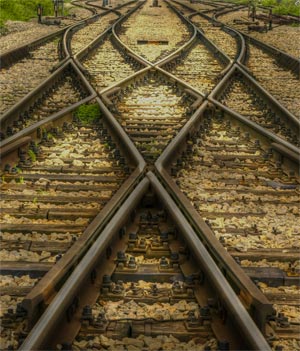

This is the world of the cross-border transaction. It isn’t just business and economics. It’s about the melding of corporate cultures and varying management styles. It’s also about politics and regulation, transparency and disclosure. And increasingly, it’s about taxes and “offshorization” of capital. Plus, many deals that would have taken place behind closed doors before are now routinely the staple of social media discussions.

For all the intrigue and uncertainty, cross-border deals are here to stay. It’s just that they are more complex—and riskier than ever. And the assessment of risk must go far beyond the conventional metrics. Many of these mergers will not succeed, or at least will go through serious growing pains before reaching equilibrium—as some of the most high-profile deals of the past few years have shown. It takes a clear vision of the benefits and a clear path to reaching those benefits to make a deal successful. Along with good timing—and possibly even some good luck.

DEAL OF THE CENTURY

The October 2012 tie-up between Russia’s Rosneft and the UK’s BP was hailed as “the deal of the century.” In a national TV broadcast, Russian president Vladimir Putin described it as “a good big deal which is important not only for Russia’s energy sector but for the entire Russian economy.” It was a complicated transaction. Rosneft agreed to buy TNK-BP, Russia’s third-largest oil producer, from BP and AAR—a Russian oil producer owned by Mikhail Fridman, German Khan, Len Blavatnik and Viktor Vekselberg—in the country’s biggest-ever acquisition. AAR received $28 billion in cash. BP, the troubled global energy company, received $17 billion and 12.8% of Rosneft. It also purchased $4.8 billion of Rosneft stock from the state.

In December, after the deal was completed, Putin was back in the news, asking the AAR billionaires to consider keeping their $28 billion in the country. “I hope they’ll decide in favor of investing in the Russian economy,” Putin said. The message is clear: In this day and age, there is no guarantee that domestic investment flows will stay domestic, and good investment opportunities can be found in many jurisdictions—not just the BRICs.

Putin’s comments provide a useful reminder of the ever-increasing significance of cross-border investment to global business. As markets—and consequently asset valuations—rise and fall, global corporates and investors are on the watch for the next good buy. And that good buy could be anywhere, geographically.

“Infrastructure deals in emerging markets are rife with political risk”

—Karthik Balakrishnan, Globescape Capital

In 2011, cross-border M&A accounted for $525.9 billion, well below the trillion-dollar high of 2007. But, despite a third quarter in which volumes fell 23%, the overall numbers for full-year 2012 are likely to be about the same as in 2011. And 2013 should see those figures start to rise again. “In this global economy, cross-border investments, in spite of temporary glitches, will continue to grow in importance,” says Hiren Ved, co-founder and CIO of Alchemy Capital, a Mumbai asset management company. “Companies need to go cross-border to acquire access to customers and markets and to acquire technology,” he says.

Also driving the cross-border deal is the need for growth. Big corporations and large asset managers, especially private equity funds, are sitting on giant pools of unused cash. Deploying that cash in transactions across borders can be a cost-effective way to expand their business and finesse many of the legal and regulatory issues that often accompany in-country transactions.

For potential targets, offer prices also are attractive, often reflecting a substantial premium to the price they could command in domestic markets. In June 2012, Chinese oil conglomerate CNOOC offered to buy Canadian firm Nexen for $15.1 billion. The offer price was 66% higher than Nexen’s trading range on the New York Stock Exchange had been in the prior 20 trading days. “This transaction delivers significant and immediate value to Nexen shareholders,” said Kevin Reinhart, president and CEO of Nexen. In December the Canadian government approved the transaction, but prime minister Stephen Harper warned against similar deals with state-owned enterprises in the future. Canada would not deliver control of its oil sands—the world’s third-largest proven reserves of crude—to a foreign government, Harper insisted.

In April, British pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca agreed to buy US biotech firm Ardea Biosciences for $1.26 billion, at a 66% premium to Ardea’s trading price prior to the announcement. In July, GlaxoSmithKline, the British drugmaker, acquired Human Genome Sciences, a US biotechnology company, for $3 billion, at a premium of nearly 100%.

Pharmaceuticals is a prime example of a sector with growing demand for cross-border mergers. As big pharmaceutical companies find that the patents for some of their blockbuster drugs are expiring, they are desperately reaching out to replenish their drug pipelines. And acquiring biotechnology companies—often in other jurisdictions—fills the need.

But as the need has grown, so has the complexity. Deals that might seem straightforward and driven by business fundamentals now are fraught with political risk and difficult cultural integration.

Ved believes the biggest deals are least likely to succeed, especially because there are so many variables to contend with: from the integration of management and business styles to the melding of technology and the workforce. “Size matters—the smaller the acquisition, the higher the probability of success,” he says.

“Timing matters too,” Ved adds. Quite often deals come unraveled because the regulatory climate is inclement. But under the right conditions political pressure will permit deals that under ordinary circumstances would face harsh trials. In December the US Federal Committee on Foreign Investment cleared the acquisition of Complete Genomics, a Californian DNA sequencing company, by BGI-Shenzhen, a Chinese operator of genome sequencing centers. Much of the criticism of the acquisition came from Illumina, a San Diego firm that is among the leaders in genome sequencers. The company had argued that the acquisition would transfer proprietary genomic technology and manufacturing know-how to the Chinese, who then could use it to undercut Illumina on price. It also argued that BGI’s access to DNA data of Americans might enable it to create a database of genetic information that the Chinese could then use to manufacture low-cost drugs and diagnostic tests.

At another time, such arguments might have won over the Committee on Foreign Investment. But with US-China business relations at a precarious junction and little demonstrable harm from the acquisition, the deal passed.

POLITICAL RISK

In contrast, in 2010, India’s GMR won the mandate for the operations and expansion of the Male airport in the Maldives. The $500 million, 25-year project was to be the single largest private investment in the Maldives—a deal that was won competitively and vetted by the International Finance Corporation. But the deal unraveled in less than three years.

“Infrastructure deals in emerging markets are rife with political risk,” says Karthik Balakrishnan of emerging markets advisory firm Globescape Capital. Deals can come apart because of changes in political leadership, because the economic targets have changed, or sometimes because the company is seen as an interloper, even a colonizer. In the case of GMR’s involvement in the Maldives, all of these happened at once.

In winning the bid to operate the Male airport, GMR beat out a Turkish-French consortium, agreeing to pay the government a fee of $78 million and also agreeing to pay 1% of the non-fuel and 15% of the fuel revenue to the government. The fees would rise to 10% and 27% in 2015. The company also initiated a $25 airport tax to offset the cost of expanding the airport. The deal was welcomed by former Maldives president Mohamed Nasheed. It was signed June 2010.

But within the year, there was discontent. On the business side, there was the feeling that the Indian company was not paying enough. On the political side, there were charges that the airport had become a fueling base for Israeli jets. Then when president Nasheed was deposed in a coup in February 2012, everything collapsed. The new government of president Mohammed Waheed Hassan went to court to take back the contract. But when the courts dallied, the new cabinet voted to deny GMR the right to operate the airport, and on December 6, 2012, the Singapore Court of Appeals—where the case was being considered—gave the green light for the government to take over.

As politics helped derail the GMR deal, politics and cultural conflicts continue to weigh heavily on ArcelorMittal, the result of a 2006 merger of Arcelor and Mittal Steel, and on the company’s operations in France. The problems within the European economy and France’s own high unemployment have also contributed.

“In this global economy, cross-border investments, in spite of temporary glitches, will continue to grow in importance”

—Hiren Ved, Alchemy Capital

The merger between Mittal Steel, the upstart steel conglomerate cobbled together by Indian entrepreneur Lakshmi Mittal, and Arcelor, the pan-European steel firm that was the world’s largest steel company at the time, was troubled from the very start. Arcelor executives did not want Mittal Steel as their owner, and they certainly didn’t want the flamboyant and high-living Lakshmi Mittal as the head of the merged entity.

In January 2006, as Arcelor struggled amid a floundering European economy, Mittal made an unsolicited bid for Arcelor, a bid that the board initially ridiculed and turned down. The management instead sought an alliance with Russian steelmaker Sevarstal to ward off Mittal’s overtures. But in the end, Arcelor’s shareholders prevailed and accepted Mittal’s $33 billion bid.

That was six years ago. Buttressed by cheap credit and a strong demand for steel, Mittal was on top of the world. In 2010, Goldman Sachs appointed Lakshmi Mittal to its board. (Mittal is only the second Indian to be on Goldman’s board. The first, Rajat Gupta, was recently sentenced to two years in prison for illegally passing information to a hedge fund manager.)

But in today’s “flat world,” nothing is certain. With the European economy still suffering and demand for steel plummeting, ArcelorMittal is now floundering. Its revenue for the nine months ended September 30, 2012, declined to $64.9 billion, from $71.5 billion in 2011, and profit fell to $261 million from $3.3 billion over the same period. With $23 billion in debt and its bonds rated as junk, ArcelorMittal started to scale down. It announced it would close one of its foundries in Florange, France, a move that would eliminate more than 600 jobs. And that’s when the roof fell in.

The French government stepped in, declaring that ArcelorMittal had acted in bad faith and gone back on its earlier promises. “We don’t want Mittal in France because they haven’t respected France,” the industry minister, Arnaud Montebourg, said in an interview published in the daily paper, Les Échos. Montebourg even threatened to nationalize Arcelor’s facilities in France if it didn’t agree to abandon the layoffs.

ArcelorMittal’s experiences in France are now commonplace to the cross-border experience. Although it was the synergies of a consolidated company that brought Arcelor and Mittal together, it was eventually the dark shadow of a depressed European economy combined with France’s own economic problems and large labor layoffs that threw the deal into a tailspin.

“Many cross-border deals offer no advantages at all,” says Andre Cappon of consultancy the CBM Group. Cappon believes that many international mergers, especially when it comes to financial exchanges, have been patched together to benefit the bankers and advisers who put such deals together and top managers who receive options to consummate such deals. Rather, he argues, there should be consolidation among domestic exchanges—and seldom beyond that. Most countries, especially in the emerging and frontier markets, don’t need two exchanges, says Cappon. And many countries can benefit by consolidating domestic exchanges to create greater efficiencies and use technology more effectively.

Cappon’s firm was the adviser to the Toronto Stock Exchange as it fought a takeover by the London Stock Exchange. “One of the premises behind the takeover was that it would give Canadian companies listed in Toronto wider access to investors and to markets,” says Cappon. But big Canadian companies already have access to global investors through Toronto. Going to London would simply have increased their regulatory burdens without any demonstrable benefits. “In situations such as these, in-country M&As make more sense,” explains Cappon.

The trend toward cross-border M&A is not likely to go away soon. Indeed, the volume and number of cross-border deals continues to grow, even in a year in which global M&A transactions are declining. Many of them will fail, says Globescape’s Balakrishnan. But those that succeed will have done so because both parties have shared the risks and the rewards and made commitments for the long-term.

There is also the need for greater adaptation. “You can’t go in there and unilaterally impose your management style and your values without compromise,” concludes Balakrishnan. “The acquirer, too, has to change.”