How companies are adapting to aging populations around the world with new products, new personnel policies and new marketing tactics.

On the one hand, the declining birthrate and the shrinking population of working age people in many countries present challenges to finding sufficient manpower to staff factories and offices to meet existing demand. Companies and governments alike are struggling to find ways to keep their older workers on the job longer. But perhaps more important for CFOs and executives mapping long-term strategies, the aging population today is healthier and wealthier than in the past and holds huge potential as a market for new products and services.

Companies faced with slack demand for such things as diapers and baby food are rolling out incontinence products and protein drinks to support aging bodies. With many aging individuals remaining healthy into their 90s, demand is increasing for everything from travel programs aimed at older audiences to aesthetic surgery to remove double chins and wrinkles. As the TV program The Golden Bachelor has demonstrated in the US, demand for dating services for people over 65 is soaring.

“Globally, this age group is the most important consumer growth market over the next 15 years,” advertising firm Ogilvy says. “Developed economies are already experiencing the huge spending power of the elderly. Asia will be no different—with the exception that the demographic changes in Asia will mean that it happens even faster in Asia.”

The cause of this business rethink is a truly striking demographic shift: The World Health Organization forecasts that the proportion of the global population over 60 years old will nearly double between 2015 and 2050, reaching 2.1 billion people. The shift is even more acute in a handful of countries: According to the World Bank’s figures, as of 2022, 30% of Japan’s population was 65 or older, while in Italy it was about 24%, prompting Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni to lament that the country is “destined to disappear.” In China, while still a relatively low 15% of the population, about 210 million people are currently over the age of 65, according to a 2023 Chinese government report—a consumer market nearly the size of Brazil’s entire population. In China and many other countries, the fastest-growing demographic is over 80.

While in the past, older consumers were often ignored because they subsisted on pensions and didn’t spend their savings as much as younger cohorts, that picture has changed dramatically as well.

“If you ask where the money is—in America, 70% of disposable income is held by people 60 and over,” says Michael W. Hodin, CEO of the Global Coalition on Aging. “Where is the business opportunity? In China, Japan or across Europe, the data points are the same.”

Japan And China At The Forefront

For example, total disposable income in the Asia-Pacific region is expected to more than double between 2021 and 2040, according to research firm Euromonitor International. “Seniors’ consumption may grow twice as fast as that of the rest of the population in many Asian countries,” says consulting firm McKinsey in a 2021 discussion paper titled “Beyond Income: Redrawing Asia’s Consumer Map.” The authors add that “by 2030, more than 95% of seniors in Australia, Japan and South Korea are expected to be online,” while “the share in China could exceed two-thirds” of the over-60 population.

The significance of the enormous elderly market in China was underscored when the government in Beijing released a white paper in January titled “Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Developing a Silver Economy to Improve the Wellbeing of the Elderly,” with a comprehensive program to ramp up senior-focused support systems, services and infrastructure, as well as products focused on the elderly.

In addition to broadening consumption and supply channels for the elderly, the government says it will boost research into clothing, shoes and hats specifically for the aging consumer and help develop health food products “suitable for the chewing, swallowing and nutritional requirements of the elderly,” as well as “suitable” literature, sports events, TV programs and other entertainment options.

While the new program will provide investment funding, the private sector in China has been focused on the aging segment for some time. “In recent years there has been a spike in the availability of products and services aimed at the aging consumer, especially for things like nutrition products, personal health and adult diapers,” says Viktor Rojkov, assistant manager of the international business advisory team at consultancy Dezan Shira’s Shanghai office. He estimates the senior market size at $680billion-$700 billion.

Shanghai has an elderly population of 5.6 million out of about 30 million in total. As in other major Chinese cities, many elderly had worked in export-based factories for decades, accumulating savings, and now had substantial disposable income to spend on new products, Rojkov says. One reason Chinese consumers are switching to online shopping, he says, is a “shame factor” for buying embarrassing products like hearing aids and adult diapers in crowded stores.

Shameless Shopping

To help facilitate online shopping for this crucial cohort, companies such as Easyfone have introduced a number of mobile phone models specifically designed for older adult users, with louder volume, larger displays, simpler interfaces, optional photos instead of numbers for speed dialing, and built-in health monitoring.

Indeed, because Japan and South Korea also have large elderly populations, phone manufacturers in those countries are increasingly turning out products specifically for that audience. Japan’s Panasonic, for example, has produced a smart stick, an intelligent cane that helps provide balance assistance and sends alerts if the user falls.

In the same context, Japan’s GLM, a Kyoto-based manufacturer of electric vehicles, produces an advanced mobility scooter that is “not just a vehicle for the elderly, but a car that makes people want to drive it, even if they have to give up their car license,” according to Fortmarei, who designed it, although the elderly might be challenged riding it as well.

It’s no coincidence that these products are aimed at the only consumer segment growing in Japan. Consumers ages 60 and older accounted for 48% of Japan’s overall personal consumption as of 2015, growing at an average rate of 4.4% per year between 2010 and 2014, according to nippon.com. Spending by households headed by someone under 60 actually declined by an annual average of 1.9% between 2003 and 2014, says the nippon.com report.

Japanese companies have responded by producing things like washing machines and microwaves that are voice operated and smaller, to match the reduced stature of aging consumers.

One of the biggest areas for growth is the market for nutrition products aimed directly at the aging. According to Polaris Market Research, the global market for these products, valued at $18.5 billion in 2022, is expected to experience compound average annual growth of 6.5%, reaching $30.6 billion by 2030. It’s no wonder that Abbott Laboratories said in 2022 that it was discontinuing its infant nutrition products in China and will replace them with adult nutrition.

Companies are also looking at beauty products focused on older women. For example, SK-II is a luxury Japanese cosmetics brand owned by multinational Procter & Gamble that uses a yeast found in the brewing of sake as a special anti-aging ingredient.

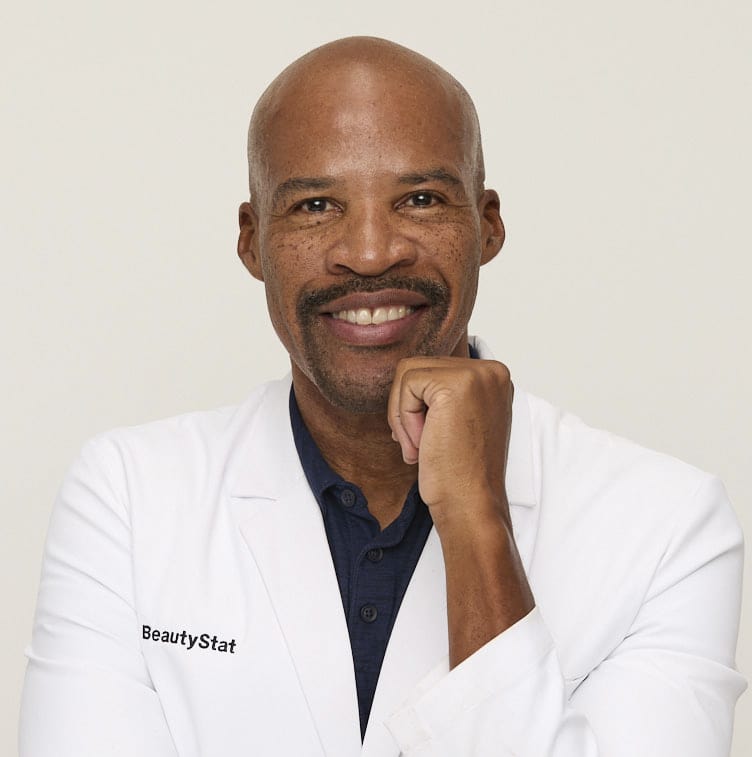

Ron Robinson, CEO of New York–based BeautyStat Cosmetics, says his firm is focused squarely on the aging market. The company is producing a moisturizer that contains two peptides that work to relax the look of expression lines and wrinkles, providing an alternative to Botox injections.

“With this launch, we are showcasing older female consumers and showing them in a sexy, exciting, vibrant way,” Robinson says. “Our research shows that women in the 50-plus group have the most disposable income, and that’s why we’re focusing on them.”

Another major issue companies face from the demographic shift is a marked decline in the number of younger people entering the workforce to replace retiring employees. In Germany, for example, the country is losing 700,000 workers a year who are not being replaced, says Erik-Jan van Harn, an analyst at Rabobank.

Enticements To Work

To encourage workers to stay on the job longer, carmaker BMW offers employees a range of health benefits designed to keep them fit, including physiotherapy at the factory. In 2019, BMW introduced its Senior Experts Program to enlist retired employees with specialist experience or years in management positions to mentor younger employees for up to several months.

Singapore, where almost a quarter of the population is expected to be over 65 by 2030, also faces a similar problem of a declining workforce. Finance Minister Lawrence Wong said in a 2021 speech that the aging of society was one of the country’s greatest challenges. He pointed out that the government was giving grants to incentivize companies to employ older workers, and at the same time it was raising the retirement age. It has also urged companies to shift away from labor-intensive manual manufacturing processes in preparation for a future workforce squeeze.

“The demographic curve may be inevitable, but it is a window of opportunity, too,” Wong said. “It is on us to find the silver lining.”

A similar problem exists in Japan but on a much bigger scale. By 2045, Japan’s population is expected to decline from its current 123 million to 107 million, according to Rajiv Biswas, chief Asia-Pacific economist for S&P Global Market Intelligence. “Japan is trying to do economic reforms to increase the female participation rate in the workforce to try to mitigate the impact of aging demographics,” he says. “But it’s very difficult when you have such large declines. And the other problem is that because there’s a lack of young people entering the workforce, you have issues because there’s not enough young people to look after this very large increase in the amount of elderly.”

As a consequence, it is no surprise Japan leads the world in the production of industrial robots designed to seamlessly replace humans in factory production lines. In 2022, Japan produced 46% of the world’s robots, compared with 29% in China and 16% in the US.

The other side of the coin is that with improved health care, medical breakthroughs, and expanding life expectancy, many workers will need to work longer to cover the cost of their retirement years.

“If people keep retiring in their late 50s, but are hoping to have longevity until their 90s, that means that over half of their eligible life they will not be working,” says Abby Miller Levy, managing partner at Primetime Partners, a venture capital firm investing in products and services for older adults.

Perhaps because of the costs, roughly a fifth of Americans ages 65 and older were employed in 2023—nearly double those who had a job 35 years ago, according to the Pew Research Center. Pew says 62% of older workers are working full time, compared with 47% in 1987.

One growth area Levy mentions is startups such as 55/Redefined and Rest Less in the UK that work to find older workers jobs or help companies present their employees with career paths long before they reach the normal retirement age, to extend their time in the company.

Peter Hubbell, CEO of marketing consultancy BoomAgers, which focuses on the elderly, says that many big firms have been slow to grasp the enormous potential opportunity in the over-65 market because of a cultural bias favoring youth over age. “All of the marketing best practices, tools and techniques were developed and optimized for the 18-to-49 cohort, and they have never really known how to market for the 50-plus segment,” Hubbell says.

He adds that companies need to “embrace the fact that there is a significant business opportunity here and that we can’t write off people because they are north of 50. Old people aren’t old anymore—they are people with money who are determined to live active, vital lives and be recognized and appreciated.”